商場本源追問 : 斷裂的城市空間與社區認同 | Trailing the Essence of Shopping Malls: The Decline of Community Identity and Erosion of Public Life

二零一七年數據顯示,香港商場密度曾冠絕全球,每平方英里約有一個商場 [1] 。從殖民時期的購物拱廊、百貨公司,到國際化消費中心,商場的演變史亦是社區公共生活的縮影。在人均休憩空間用地不足三平方米的香港,商場作為多功能消費場所遍及各區域,已經完全融入人們的日常生活。

大家是否還記得:

兒時跟家人一起逛百貨公司選購傢私的那種興奮

新年買新皮鞋和衣服的激動

約朋友一起看電影、溜冰、飲茶的喜悅

GUTS MALL RESEARCH SPARKS,2025(圖片來源/ GUTS)

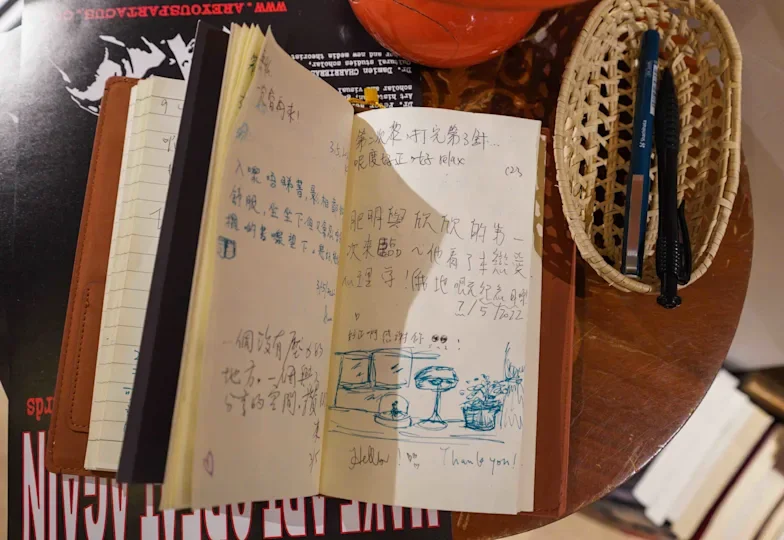

GUTS吉人吉事通過前幾期的線上互動(GUTS Sparks)收集了大家的商場記憶,本文將基於你們的聲音,深入探索香港商場的發展與正在面對的挑戰。

(閱讀時間:13分鐘)

商場的前身 —「公共市場」/「步行長廊」/「室內烏托邦」

追溯商場的起源,如同在追溯購買產品和服務的場所-最早出現這些行為的空間並不是我們所熟知的商場,而是從古代就形成的、形式和規模大小不一的公共市場,除了消費行為,亦有許多日常閒談以及社交時刻在此發生。

其後,是伴隨城市發展而形成的「城市長廊」— 一個線性的半室外空間,也是於十八世紀末誕生的購物拱廊,其目的是為了讓行人在交通繁忙的路面上仍能安全地閑逛 [2] 。

左圖:意大利Trajan's Market位於古羅馬中心,早在西元110年就成為瀏覽商品的熱門場所(圖片來源/ wikipedia)。右圖:香港中環德輔道一帶也引進了西式購物走廊的概念,此為1931年代的告羅士打行。(圖片來源/ etnet 經濟通)

現代化商場的發展始於一九五零年代的郊區化浪潮。一個全封閉式的購物設施Southdale Centre於一九五六年首次出現,這個來自美國的獨立商場,可說是現代商場的起源。建築師 Victor Gruen亦被稱為「郊區購物中心之父」,其初衷是為了把城市街區中的公共娛樂場所(如廣場、社區中心、郵局等)帶入郊區的一個密封購物設施中,創造一個多元且步行友善的室內「城鎮中心」,兼具休憩和社交的功能,保護行人不受汽車、煙霧和噪音的困擾。現代化商場的原型好像一個「四季如春」的室內街區,除了瀏覽商品,亦承擔著促進社交和連結社區的功能。

1956年代的Southdale Centre ,除了商鋪,還設置了眾多景點例如鳥舍和噴泉等,並被住宅、辦公樓、醫療設施、學校等社區設施包圍,鼓勵市民選擇步行而非汽車出行。(圖片來源/ Life Magazine Photo Archive)

香港商場— 城市空間商業化、去社區化的伏筆

香港商場化路線和其他地區有些不同,除了是世界上人口密度最高的城市之一外,市區內可發展的土地有限且昂貴,且市民出行高度依賴公共交通,因此香港的商場大部分不像其他國家一般的獨立建築物,而是位於大廈低層或基座,連同住宅辦公等其他一起綜合發展,很少獨立存在。

全球第一家現代化商場在美國落成之時,香港也進入了商場發展的轉型過渡階段:出現了由唐樓重建的新式住宅—香檳大廈,最低兩層是零售空間,是香港第一個連同住宅一併發展的商場;由街鋪進化而成的萬宜大廈,是香港首個與現代辦公室一起發展並具一定規模的商場。

左圖:香檳大廈除了底下兩零售空間外,樓上住宅亦安裝了早期香港住宅較少出現的冷氣機,設備先進(圖片來源/ Being Hong Kong)。右圖:德輔道中的萬宜大廈是全港第一幢安裝自動扶手電梯的建築物。(圖片和資訊來源/ oldhkphoto.com)

截止此階段,香港的商場還沒有出現顯著的公共空間和便民設施;直至一九六六年,尖沙咀海旁的海運大廈成為香港首座專為消費而設的大型商場,促進了香港商場化的進程,也為後續香港多數商場以上流社會和外地遊客為主要服務對象埋下伏筆 [2] 。

左圖:1980年代的海運大廈(圖片來源/ 昔日香港)。右圖:1980年代海運大廈的玩具反斗城旗艦店,成為中產家庭的親子朝聖地。(圖片和資訊來源/ 當代中國)

一九七零年代末,香港開始實施「綜合發展區」(Comprehensive Development Area,CDA)的城市規劃概念,為了增加土地使用效率,由擁有足夠業權的發展商主導,在建造牟利的住宅、商場、辦公室時,必須預留地方作政府、機構和社區設施、運輸及公共交通設施及休憩用地。CDA於此後的十五年間有計劃地於全港展開,私營購物場所在同時期越來越流行。

“香港百花齊放的購物中心和商場於八十年代成功成為市民生活密不可分的一部分,更是市民心中極具吸引力的公共空間。”

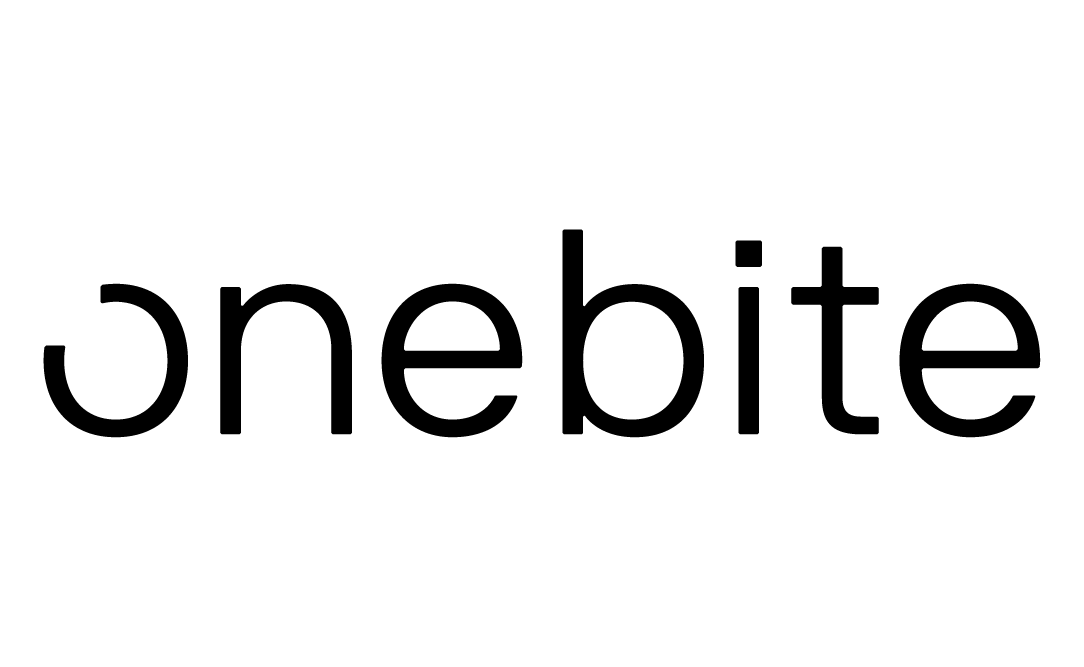

香港將軍澳八十六地段夢幻之城為一大型綜合性住宅區規劃項目,佔地約34.8公頃,提拱50幢約21,500個單位的住宅大樓,40,000平方米商業及其他設施,包括學校、公交、室內康樂及政府公用設施。(圖片來源/ Wong & Ouyang (HK) LTD)

然而,在第二週的GUTS Sparks,我們竟然收到不少這樣的回覆:

「經常去的商場都只是被迫路過而已」

「去商場只為了去樓下個超市」

「因為有馬莎才經常去」

「空鋪變多了就不去了」

「鋪頭種類好單一,一點購物慾都沒有」

曾經的活力及吸引力怎麼會消退至此?「綜合發展區」實施後,香港出現的商場綜合體逐漸變得越來越大而同質化,人們回家不再經過街道,而是一個個封閉的商場。二零零三年的「自由行」政策導致越來越多的商場以旅客作為主要服務對象,紛紛提高商鋪的檔次,使得市民認為商場的店鋪與商品並不符合他們生活所需 。

其後,二零零五年,香港的公屋商場開始「私有化」,意味著這些商場會以商業的模式營運,具有特色或是社區所需的的小本店鋪逐漸被大型連鎖店取代。除此之外,商場內的公共空間也在由私營機構管理後,變為「私有的類公共空間」(Privately Owned Public Space,POPS)[2],方便管理及利益優先的原則導致商場內許多服務大眾的設施逐漸消失,亦包含如溜冰場、戲院甚至過山車等娛樂設施,這些空間逐漸被騰空變成展銷活動的場所。香港的商場在此後變得越來越商業化,甚至引起市民厭惡。

禾輋商場過去的設計重視生活化場景,充滿平民生活氣息,但由私營機構接管後,空間設計和活動運營都變成高檔格調,租金的提高也導致做小本生意的民生小店撤離商場。有舊居民提到「這樣千篇一律、毫無性格的商場放在平民百姓蝸居裏,變得不倫不類」。(圖片來源/首二百萬公共屋邨居民, Zebedee Ma )

二零一零年後,各商場開始採取多種策略,試圖挽回失去的人流:引入以本土品牌和創意手作為賣點的市集、將商場分拆成密集而狹小的鋪位出售、重視旅客零售......這些策略逐漸演變成市集的同質化、管理不佳的劏場、本地市民找不到去商場的慾望......

尖沙咀首都廣場是典型的劏鋪式商場,業權分散的特點導致活動和管理都很難進行,也是大多數劏場發展緩慢的原因。(圖片來源/ South China Morning Post via Getty Images)

受歡迎的「現代商場」?

隨著一棟棟同質化商場在城市中出現,一部分看上去失去競爭力的商場正在或曾經努力「堅守」,仍有人會定期拜訪並吸引市民關注。它們在某種程度上,仍然作為一些人的「社區記憶載體」而存在。

炮台山富利來商場曾經有民間發起並引進文青店鋪的活化計劃,一度讓商場充滿人氣;灣仔東方188仍有為街坊和熟客服務的咖啡店、水族鋪及二手CD玩具鋪;遊戲卡牌愛好者仍會在天悅廣場的走廊上競技和活動;即將被拆掉的九龍城廣場仍然會因為短暫的中庭活動而吸引眾多人前來......[3]

炮台山富利來商場曾經有民間發起的「富利來活化計劃」,引進十多間文藝小鋪,類型多元,有供人停留的全自助書店,也有販售香港不同年代玩具的店鋪,以及主題多樣的展覽空間及工作坊。(圖片來源/ Hong Kong D & Davies)

灣仔東方188商場共有兩層,每層客人雖不算多,但拜訪者大多數都是店家的熟客,還會在店鋪門口的座椅上聊聊天。(圖片來源/ GUTS)

受歡迎的現代商場往往不僅販售商品,更販售一種現代生活的體驗與歸屬感,除了一些仍有本地特色的商場,還有一些提供貼合市民空間需求的商場。例如IFC商場除了是消費場所,亦有景觀天台供上班族吃午餐和休息,以及受年輕人歡迎的希慎廣場亦有戶外滑板場和休憩平台[3] 。

左圖:IFC商場內的戶外天台有免費的桌椅供周圍上班族和居民吃午餐、休息閑聊(圖片來源/ GUTS)。右圖:希慎廣場四樓的免費滑板場一直都備受歡迎(圖片來源/ Healpy Post)。

值得一提的是,商場(Shopping Mall)—最開始在西方的術語是「步行長廊」(Pedestrian Promenades),除了遮風避雨,更重要的是能創造吸引人的步行環境、停留休息的場所、社交相遇的機會,而商鋪只是其中一個吸引人的要素,並不是這個空間的全部。

迄今,那些從前的社區場所逐漸從日常對話淡出,變成大家口中「返屋企被迫經過」[3] 的同質化商場、逐漸蔓延開變成倉庫的空鋪、變成通道的商場。市民失去的不僅是一個消費場所,而是一個曾經能產生社區共鳴的公共場域。

註:

[1] 部分數據來源 Mall City: Hong Kong's Dreamworlds of Consumption,Stefan Al, 2016

[2] 部分數據來源:香港商場的黃金時代,何尚衡,2024

[3] 信息來源:GUTS Mall Research Sparks

Trailing the Essence of Shopping Malls: The Decline of Community Identity and Erosion of Public Life

2017 statistics revealed that Hong Kong boasted some of the highest densities of shopping malls globally, with approximately one mall per square mile [1]. From colonial-era shopping arcades and department stores to contemporary international retail hubs, one could argue that the evolution of shopping malls mirrors the transformation of public life in Hong Kong. In a city where public space per capita is less than three square meters, malls have become ubiquitous, multifunctional venues woven into the fabric of daily life. Many of us fondly recall childhood trips to department stores to shop for furniture, the excitement of buying new shoes and clothes for Lunar New Year, the joy of catching a movie, ice skating, or having dim sum with friends and family.

Through previous GUTS online interactions, we have gathered collective memories and aspirations about malls from our readers. Shaped by these voices, this article delves into the development of Hong Kong’s shopping malls and the challenges they face today.

Predecessors of Shopping Malls: “Public Markets”, “Arcades”, and “Indoor Utopias”

Tracing the origins of shopping malls takes us back to the spaces where people first engaged in the transactions of goods and services. These were not the malls we know today, but public markets that varied in size and form. Beyond commerce, they were hubs for social exchange and daily interactions. Urban development later gave rise to "city arcades"—linear, semi-outdoor spaces that emerged in the late 18th century as shopping arcades. Designed to provide pedestrians with a safe environment away from busy traffic, these spaces became precursors to modern malls [2]. In the 1930s, Hong Kong’s Central district adopted the concept of Western-style shopping arcades.

The development of modern shopping malls began in the 1950s along with the wave of suburbanization. Among these, the Southdale Centre, which opened in the United States in 1956, was crowned as the world’s first fully enclosed shopping facility. Designed by architect Victor Gruen, often called the "Father of Suburban Shopping Malls," Southdale aimed to recreate the communal and recreational aspects of city neighbourhoods within a suburban, enclosed setting. Gruen envisioned malls as vibrant indoor “town centres” where people could shop, socialise, and relax in a pedestrian-friendly environment, shielded from cars, smog, and noise. These early malls, with attractions like birdhouses, fountains, and community facilities, were surrounded by residential, office, and community infrastructure such as schools and medical facilities, encouraging citizens to walk instead of driving. The prototype of a modern mall was akin to an “ever-spring” indoor town square, fostering commerce, social and community connection.

Hong Kong’s Malls: Commercialisation and Stripping of Communal Urban Spaces

Hong Kong’s mall development followed a unique trajectory due to its high population density, limited developable land, and heavy reliance on public transportation. Unlike standalone malls in other countries, most malls in Hong Kong are integrated into mixed-use developments, occupying the lower floors of residential or office towers.

As the modern shopping mall debuted in the U.S., Hong Kong underwent a similar transformation. The Champagne Court, a redeveloped residential building, became the city’s first mall integrated with housing. Similarly, the Man Yee Building evolved from street-level shops into Hong Kong’s first modern office-mall complex. However, malls during this phase lacked significant public spaces or community amenities. In 1966, the Ocean Terminal in Tsim Sha Tsui became Hong Kong’s first large-scale mall dedicated exclusively to shopping. This development accelerated the city’s mall-ization process and set the precedent for malls catering primarily to affluent locals and tourists [2].

By the late 1970s, Hong Kong adopted the "Comprehensive Development Area" (CDA) planning concept. To maximise land utilisation, developers with adequate ownership were required to allocate space for government, institutional, and community facilities, transport and public recreation, whilst developing for-profit residential units, malls and offices. Over the next 15 years, this approach facilitated the proliferation of a plethora of private shopping malls in the city. By the 1980s, shopping malls had become integral to Hongkongers’ daily life, and had transformed into the city’s “most attractive public spaces” for many.

However, reactions from GUTS Sparks (GUTS’ interactive Instagram stories) reveal a significant shift in perceptions of shopping malls: “I only pass through malls because I have to.”; “I visit the mall just to get to the supermarket.”; “I only go there because of Marks & Spencer.”; “With more vacancies, I stopped going to malls.”; “The variety of stores is so limited—I don’t even feel like shopping anymore” [3]. What caused such a decline in vibrancy and appeal?

After the implementation of CDA, malls in Hong Kong became increasingly large and homogeneous. People no longer walked through lively streets to get home, but instead passed through enclosed shopping centres. Furthermore, the 2003 "Individual Visit Scheme" attracted a surge of mainland tourists, which shifted mall priorities towards luxury retail, catering to visitors rather than locals. Many residents felt that mall offerings no longer aligned with their daily needs. In 2005, the privatisation of public housing malls further commercialised these spaces, favouring large chain stores over small, community-oriented businesses.

Additionally, with private management taking over more shopping malls, spaces that were once public areas were being converted into "privately owned public spaces" (POPS) [2]. With profit as the maxim, many entertainment and communal facilities serving the public—such as ice rinks, cinemas, and even roller coasters—were removed, replaced by venues for sales exhibitions. Over time, malls became purely commercial, leading to public discontent.

Post-2010, malls adopted various strategies to regain foot traffic, for instance, introducing local craft markets, subdividing retail spaces, and catering to tourists. However, these efforts often led to almost identical bazaars, poorly-managed shop clusters, and a lack of appeal for local residents. Online shopping, cross-border consumption, and the COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated the decline, leaving malls struggling to retain their once-central role as vibrant urban public spaces.

Modern Malls That Resonate with Communities

Despite the rise of homogeneous malls, some have managed to retain their charm or adapt meaningfully to community needs. These malls continue to serve as "repositories of community memories." Fu Lee Loy Shopping Centre in Fortress Hill was briefly revitalised by grassroots initiatives, introducing local artisan shops and attracting crowds. Oriental 188 Shopping Centre in Wanchai still hosts neighbourhood coffee shops, aquariums, and second-hand CD and toy shops. Smiling Plaza remains a gathering spot for trading card enthusiasts. Kowloon City Plaza, slated for demolition, continues to attract crowds with temporary atrium events [3].

Successful modern malls are not only trading goods; they offer experiences and a sense of belonging. IFC Mall, for example, provides a rooftop garden where office workers can relax during lunch breaks. The popular Hysan Place features outdoor skate parks and rest areas, appealing to younger crowds [3].

It is worth noting that the term “shopping mall” originally referred to “pedestrian promenades.” Beyond sheltering visitors from the elements, malls were meant to create inviting pedestrian environments, resting spaces, and opportunities for social connections. Stores were merely one of the attractions, and did not define the entirety of the place.

Today, many malls have drifted far from this vision, becoming “just a passageway” [3], filled with vacant shops or bland corridors. What Hong Kong has lost is more than just a shopping venue, but public spaces that once fostered connections and a sense of shared community identity that still resonated among generations of locals.

References

[1] Data source: Mall City: Hong Kong’s Dreamworlds of Consumption, Stefan Al, 2016

[2] Data source: 香港商場的黃金時代,何尚衡,2024

[3] Information from GUTS Mall Research Sparks

你可能對以下吉人吉事有興趣:

You may also be interested in these GUTS Stories: