共居,只是另一種劏房?|Is co-living a new lifestyle–or is it simply a reiteration of sub-divided flats?

提到共居(co-living),你和我的理解或許不一樣:如果你年紀稍大、或了解香港昔日生活,未必覺得這是新鮮事,當年梳起不嫁的媽姐一起買「姑婆屋」,其實已是共居的一種;如果你是戲迷,可能會想起是枝裕和的《小偷家族》,住在一起的陌生人感情可以遠勝親人,說明「家」的條件不一定是血緣,而是人與人之間的相處;如果你是捱貴租的無殼一族,則可能認為co-living只不過是業主想出的新包裝,本質上仍是劏房。

既然不是新鮮事,當下討論「共居」的意義是什麼?「有得揀太重要了。」德國共居組織id22創辦人Michael Lafond這句話,引領我們思考:在吃力的置業租樓以外,共居會不會是出路?怎樣的共居才不是「另類劏房」?今期,我們先從起點思考,了解「共居」的概念如何誕生、社會變化如何催生共居熱潮。

六十年代萌芽

共居的起源眾說紛紜,有人追溯至遠古遊牧或中世紀時代,但較多人談論的是1960年代兩種新思潮:一是來自丹麥建築師Jan Gudmand-Hoyer,他跟友人想嘗試全新的居住模式:12座排屋(terrace house)以外,建一座共用的房子及泳池,從而建立更緊密的社區鄰里關係。當時地皮買好,政府也批准動工,可惜鄰居反對,只能作罷。

另一種說法,指共居來自女性主義。丹麥女子Bodil Graae同樣在報章撰文(Children Should Have One Hundred Parents),批評「男主外,女主內」的傳統觀念影響女性自主發展,於是提出共居模式,孩子的照顧者是社群,不是單一的媽媽,這概念得到50個家庭支持。

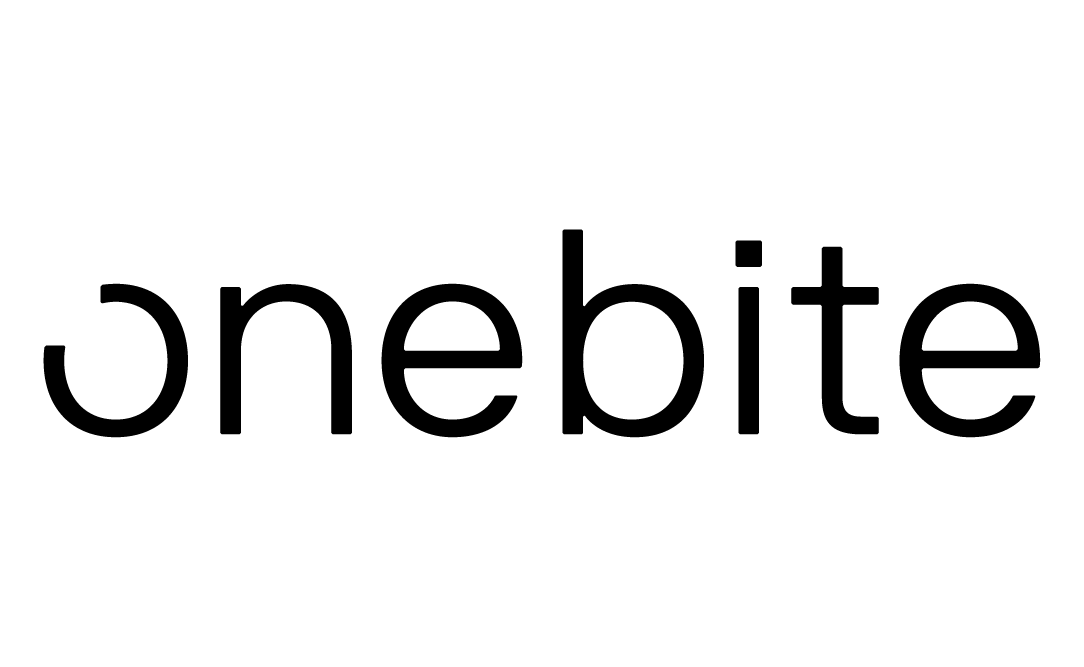

「共居」住宅項目:更抵更彈性?

由此可見,共居啟蒙自一種理想,即是「生存以上,我要好好生活」。來到最近10年,從Google環球搜尋趨勢可見,co-living自2016年起開始進入大眾視野。「共居」雖然未有放諸四海皆準的定義,但歸納各地案例,較常見的共居形態有三種:

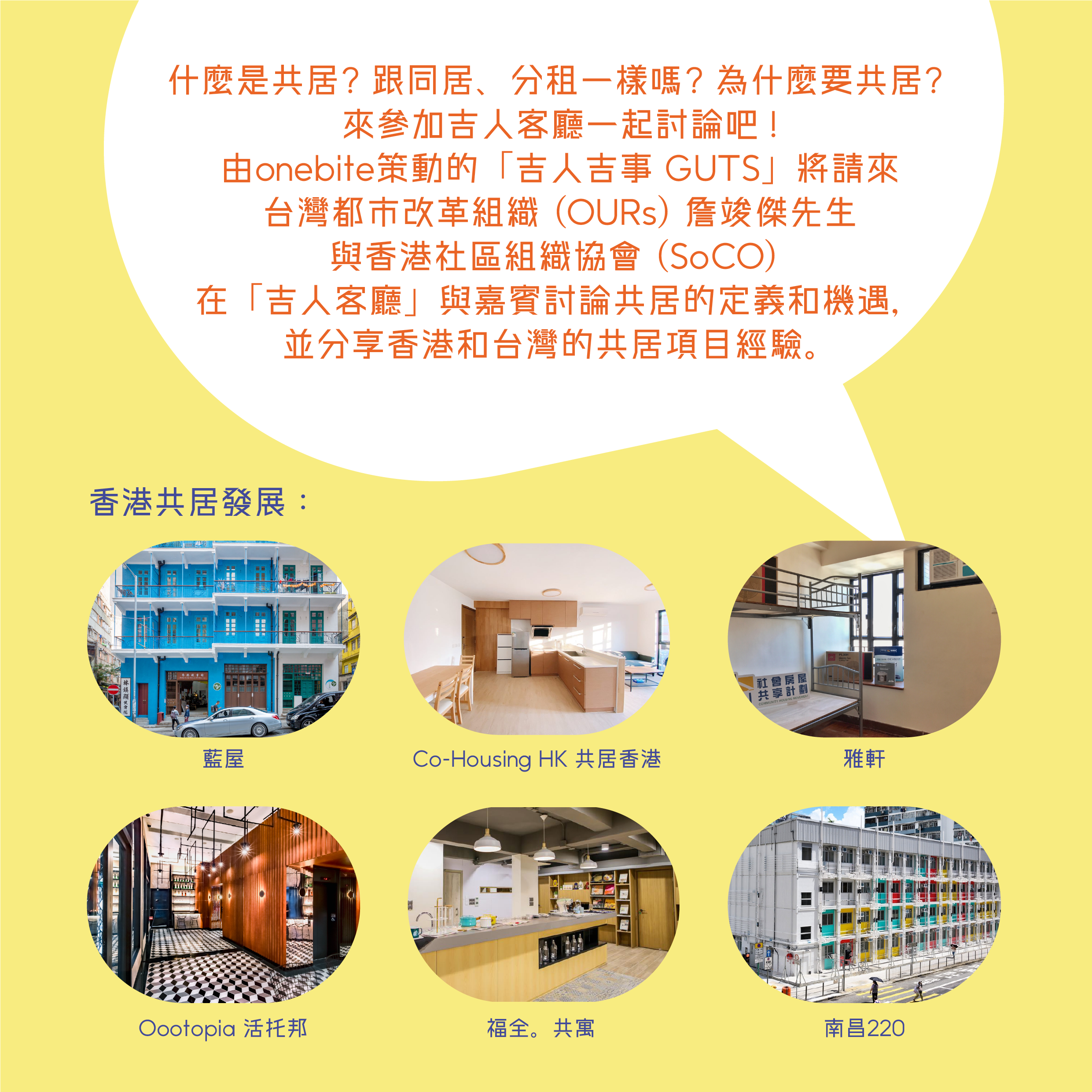

一種是商機帶動:全球各地住在大城巿的人們,也面對薪金增幅跟不上樓價的困境,在歐盟地區,愈來愈多人選擇留在城市工作,城市人口預計將由現時的75%增加至2050年的84%。有見需求巨大,財團推出「共居」單位:租約可長可短,雜費通常比獨自租屋便宜。住客在擁有私人房間以外,可以通過共享設施、參加住所活動等,建立人脈。香港也有類似的共居之選,例如Weave Living、Oootopia等,裝修時尚摩登,吸引學生及年輕白領入住。

為解決孤獨感 所以共居?

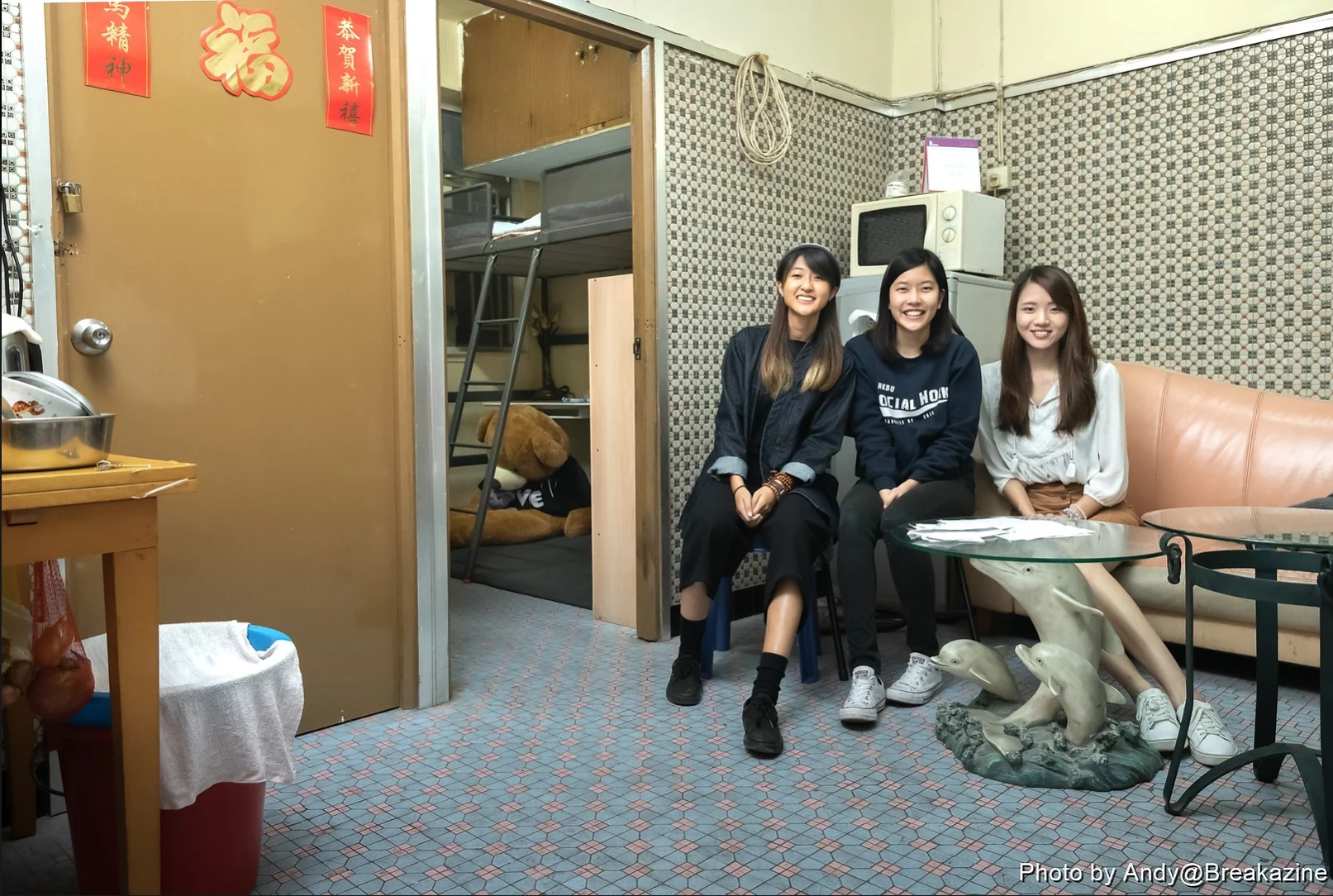

另一種共居是回應社會的多元需要:過去環球主流是結婚生子、組織家庭,但現在世情更多變:有一人家庭、單身長者、LGBTQ等,住在傳統社區或許令他們的孤獨感更重。哈佛大學2020年研究顯示,超過三分一的美國成人感受到嚴重孤獨。英國超過900萬人經常感到孤獨,政府因而在2018年設孤獨大臣一職 ,應對國民情緒問題。其中有人相信共居社群是孤獨解藥。瑞典共居房屋Färdknäppen,住客是中高齡人士,他們需要自行打掃、煮食、參加居民會議等,認真討論管理。連繫彼此的不是血緣,而是對群體的投入。本地灣仔藍屋「好鄰居計劃」 也是一例,交到租不代表可以住進去,住客需要承諾交換技能、為營造社區出力。這一類的共居較重視住客對社群的付出。

社福界介入 共居幫助邊緣社群?

還有一種源自社會公義:為什麼城市如此富裕,卻仍然有人找不到安身立命的家?2022年3月底,香港公屋平均輪候時間增至6.1年。即使是凶宅等不受歡迎單位,2021年申請仍然超額達29倍。社企、NGO、業主等遂出手,回應邊緣群體的需要,例如本地社企「要有光」,獲得良心業主支持,將單位改為「光房」,環境雅致整齊,住客主要是單親媽媽及兒女,居住年期為3年,其間獲安排參加「向上流動訓練」、「共居訓練」等課程。機構相信只要化解人們內心的絕望、過3年有尊嚴安穩的日子,人就能發展自立。這種社福界牽頭的共居模式,就是要讓所有人都有得揀兼住得好。

德國共居組織id22創辦人Lafond強調:「Social Architecture is more important than architecture of a house。」若要好的共居,人的互動比建樓更程重要。如果想探索更多香港、台灣的真實共居經驗,歡迎報名參加6月10日(五)「吉人客廳 - 線上沙龍」,了解更多:https://bit.ly/3z0dvIe

圖片:藍屋、CUP Magazine、Breakazine、網上

Different generations hold different perceptions of co-living. If you have vivid memories of the city’s way of living in the old days, you might consider co-living an old wine in a new bottle. Somehow it sounds familiar and reminds people of a “spinster house”, which means a house shared by unmarried women. Or, if you are a cine fan, the term “co-living” might bring to your mind Shoplifters, a film by Hirokazu Koreeda that depicts a family composed of strangers living under the same rooftop. The film reveals how the concept of family goes beyond the kinship system, and sheds light on the family-like bonds cultivated over shared experiences. If you find Hong Kong’s housing unaffordable and are struggling to pay high rents for an apartment, you might consider co-living an equivalent of sub-divided flats “re-branded” by lucrative landlords.

With all these different attitudes towards co-living in mind, how should we approach the notion? Why is it relevant to us all? According to Michael Lafond, the founder of id22—an organisation in Germany that advocates creative sustainability including co-living, co-living is worth exploring as it offers choices; and having the power to choose makes a difference. Hong Kong’s housing market has remained unaffordable for years, would co-living be a way out? How could co-living projects differentiate themselves from sub-divided flats? In this issue, we’re going to trace the origin of the co-living concept, and revisit the social catalysts behind the rise of the co-living trend.

The emergence of co-living in the 1960s

There are various sayings surrounding the history of co-living. While some think that the idea of co-living is a modern iteration of ancient nomads’ way of living or the communal living practices in the Middle Ages, a more popular opinion attributes the origin of co-living to two emerging schools of thoughts in the 1960s. Danish architect Jan Gudmand-Hoyer was one of the pioneers. With an aim of cultivating a close-knit neighbourhood, Gudmand-Hoyer and his friends developed a new co-housing model that involved building a common house and swimming pool alongside twelve terrace houses. Just when they had the land ready and received approval from the government, the plan came to a halt due to opposition from the neighbours.

Another saying was that co-living originated from feminism. Bodil Graae from Denmark wrote a newspaper article titled "Children Should Have One Hundred Parents”, in which Graae criticised the gender stereotypes, including the belief of “women’s place is in the kitchen”, for undermining women’s autonomy. Putting forward a co-housing concept that regarded the community as an extended family, Graae suggested the whole community could actualise the concept of collective mothering and take care of the children in the neighbourhood. A group of 50 families backed her initiative.

Do co-living residential projects offer more economic and flexible housing options?

Co-living, as a housing model motivated by ideals, aspires to improve people’s quality of life such that residents could survive and–more importantly–thrive. The Google search statistics in the recent decade reveals that co-living has become an increasingly popular concept. Though there is no universal definition of co-living so far, we come up with three common co-living models with reference to current practices around the globe.

A common co-living model is commercially driven and led by developers. Property giants are aware of homebuyers’ frustrations in the face of the ever-soaring property prices. In the European Union countries, more people prefer living in the cities; the urban population rate is, therefore, expected to increase from 75% today to 84% in 2050. Developers see huge profit potentials in this demographic trend, and started introducing co-living residential projects. They offer flexible lease terms to tenants at a relatively low cost. Residents could enjoy their own private rooms complemented with access to shared facilities. Networking opportunities are also available as residents could meet people from different walks of life at communal events. Weave Living and Oootopia in Hong Kong offer similar co-living residential projects, which appeal to students and young white-collar workers with modern and fully furnished apartments.

Is co-living a cure for loneliness?

Another co-living model is a response to people’s needs in a diverse society. Gone are the days when there was only one dominant social trend and people shared a common goal of forming a traditional family. Nowadays, people embrace a broad range of lifestyle choices and are open to fight for their rights in multiple aspects. Those who choose to live alone, or those who are part of the LGBTQ community, might feel left out in a traditional community. In the United States, a survey conducted by the Harvard University in 2020 reveals that over one-third of the respondents felt “serious loneliness”. In the United Kingdom, the position of Minister for Loneliness was set up in 2018 as over nine million of its citizens often felt lonely. Some believe that establishing a co-living community is a cure for loneliness. Färdknäppen, a co-housing initiative in Sweden, is an example. Targeting middle-aged people, the initiative requires residents to take care of their own chores; they also have to attend community meetings and be responsible for the house management. What actually links residents together is not kinship, but a shared passion towards a community. In Hong Kong, Viva Blue House has launched a similar initiative titled “Viva Blue House Good Neighbour Scheme”. It invites no ordinary tenants but passionate individuals who are willing to contribute their skills and cultivate a close community. This type of co-living scheme prioritises tenants’ commitment and contributions towards the neighbourhood.

Are co-living initiatives led by the social welfare agencies targeting the marginalised groups?

The third model of co-living initiative is driven by the pursuit of social justice. The fundamental question of housing inequality in Hong Kong is: Why is such a huge population deprived of a decent living space in this prosperous city? By the end of March 2022, the average waiting time for public rental housing in Hong Kong has climbed to 6.1 years. Even for the relatively unpopular flats, such as “haunted” units where murders have taken place, the application rate exceeded its capacity by 29 times. In view of the overwhelming housing demand, Light Be (Social Realty), a local social housing enterprise, has garnered support of generous landlords who offer their flats to be repurposed as “Light Homes”. The majority of the beneficiary households are single-mother families. Residents are given a three-year tenancy, during which various training courses, such as the “Upward Mobility Training” and “Co-housing Training”, are offered. Light Be adopts the self-sustaining operation model, and believes that the beneficiaries could develop their potentials fully and stand on their own feet if they are given room, resources, and dignity to overcome their difficult times. This co-living approach implemented by the social welfare agencies aims to offer everyone a liveable environment with quality of life.

As how Michael Lafond concludes the essence of co-living—“Social Architecture is more important than architecture of a house”. The key to a genuinely beneficial co-living model lies not in the building itself, but the interaction among the community.

In our upcoming online event “GUTS: Lounge – Online Salon” on 10 June (Fri), speakers from Hong Kong and Taiwan will share their co-living experiences. Please sign up and join us if you are interested in learning more about the topic: https://bit.ly/3z0dvIe

Image: Viva Blue House, CUP Magazine, Breakazine, Internet

你可能對以下吉人吉事有興趣:

You may also be interested in these GUTS Stories: