歐洲共居:從個人走到社群,社群再走入社區|Co-living in Europe: From individuals to neighbourhood, from neighbourhood to community

提到外國共居,很多人直覺是「易做啦,咁多地」,答案僅說對部分。在以下的歐洲案例,政府願意提供低價土地,當然是共居成功因素之一,但我們從中可以借鏡的,是建築師或地方組織如何解決現實的困難,包括最重要的經濟成本問題,然後再撮合一群想要認真生活的人,當中有基層、女性或移民。這些個案,都花了至少5年的時間磨合,從個人走到社群,社群再走入社區。讓我們問問自己:除了錢,還願意花多少心力,經營理想的家?

德國:建築師買地 居民自己裝修減成本

共居房屋Spreefeld位處德國柏林市中心,沿河而建,是昔日東德圍牆所在之地。2009年,一群建築師購下此地,因為不想當地成為倒模式商業區,經討論後決定發展共居房屋,2014年落成,當中有3個發展理念:民主管理、租金合理及環保建築。

整個項目的設計,主要是盡量減低成本,讓入住的人可以用較合理的價錢負擔,例如屋苑主要使用再生能源(慳錢!),單位裝修由居民自己負責(豐儉由人﹗)。建築師的理念,是希望項目可以容納不同形式的家庭,例如單身年輕人、獨居長者、單親家庭、大家庭等。雖然居民大部分來自中下階層,但當中仍包括有能力買下單位的業主,以及選擇付租的租客。

居民按自己對生活的追求,選擇獨立或群居單位,群居單位可住6至21人,共享客廳及廚房。

居民每月都要參加大會,商討重要決策,例如不建私家車位,鼓勵單車代步、如何管理庭園農作物等。所有人都有發言權,不是建築師或發起人說了就算。地下向公眾開放,有共享工作室、木工設備、社區廚房、孩子日託中心等,附近街坊與Spreefeld居民因而有了生活交集。

維也納:女性共居 跳出「媽媽」「OL」身分

維也納建築師Sabine Pollak長年關心住宅及女性議題,2002年開始發起[ro*sa]22行動,收集獨居女性對未來居住的想像:小公寓、有好多公共空間、租金合理等。Pollak希望建立女性共居住宅,通過「住」為女性充權。計劃得到政府支持,預留兩塊土地作建築用途,租金得到政府補貼。由構想到落成,歷時7年。女性申請租住時,組織會告知居住理念,期望彼此價值觀相近,願意參與女性為主的社群生活。

最初兩年,住客大多忙於安頓及適應,後來社區生活逐漸活絡起來,例如周末聚在工作室玩陶藝、在花園參加BB派對、室內舉辦電影放映會等。圖書館也是聚腳地,女性主義書籍是重點藏書之一。居民通過讀書會等活動,思考女性處境,討論改善方法。有女性住客分享,自己定居在此,得到很多尊重及鼓勵,人變得更有創意,故能跳出「媽媽」、「OL」的身分,嘗試做攝影師。

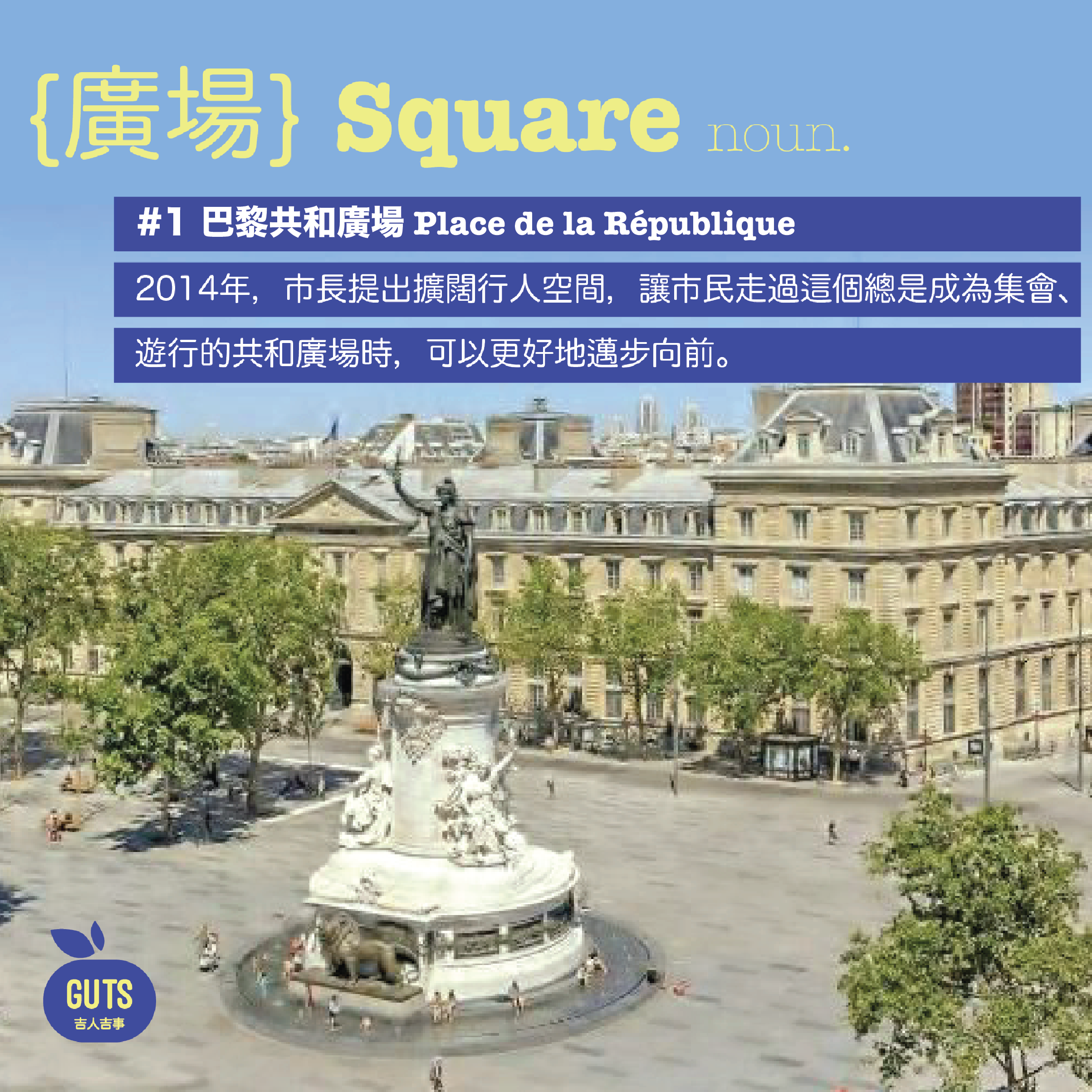

比利時:移民家庭 齊齊慳錢儲錢

很多香港人的心願是「含金鎖匙出世」,不愁住屋;在比利時布魯塞爾,也有類似的俗語:「每個比利時人出世時,肚子已藏有磚頭。」比喻國民都想盡快置業。

但事與願違,香港人與比利時人,原來都有共同命運,樓價不斷上升,公屋追不上需求。在比利時最貧窮的地區,本地人無法買屋,更何況是移民家庭。於是,就有一間社區中心名為「好日子」,先用優惠價錢向市政府買下土地,再與當地關注移民權益的組織CIRE合作,撮合多個移民家庭,組成共居群體,經常開辦工作坊、討論共居想法,累積的會議結果,最終成為建築方向,建築師繼而展開設計。

這些家庭其中一個共同決定,是選出最想要的節能設計(passive house),通過房子本身的結構及用料,達到冬暖夏涼的效果,慳電又慳錢。家庭之間亦會組成儲蓄團體,互相幫助日常花費。經歷7年的討論與工程,如今共有14個家庭搬進14間新屋。長期合作的居民顯得團結互信,一起建立社區花園,更會舉辦街頭派對,邀請附近的鄰居參與,消除本地人與移民的介蒂。

圖片:網上

What comes to your mind when you think about launching co-living projects in other countries? For many, the provision of co-living housing in foreign countries, where developable land is available in plentiful abundance, is considered an easy task. This perception is, however, only partially correct. The provision of low-cost land for housing is definitely one of the vital factors contributing to the success of overseas co-living schemes. Yet, when we take a closer look at the co-living phenomenon in Europe, we realise how architects and local organisations have also played significant roles in tackling pragmatic difficulties, such as the operation cost and the “recruitment” of like-minded residents comprised of the grassroots, women and immigrants. In this article, we will take you through several European co-living projects, in which a considerable length of time, 5 years at least, is spent to cultivate harmony among people of diverse backgrounds and cultures—and to form a close-knit neighbourhood in the community. Let us ask ourselves a question: How much, other than money, are we willing to pay in running an ideal living space we proudly call home?

Low-cost housing in Germany: Land purchased by architects while interiors fitted out and finished by residents

Spreefeld is a project for communal living located at the city centre of Berlin along the river Spree, where the Berlin Wall once stood. In 2009, a group of architects came together and formed a cooperative as they shared the same vision of the Spreefeld site that, instead of a standard business area, it could be something different. The group reached consensus after discussion, and embarked on the co-housing scheme with three key development philosophies: democratic management, affordable rent, and sustainable architecture. The construction of Spreefeld was completed in 2014.

The whole project is devised with a minimum cost to offer affordable housing. For instance, renewable energy technologies are incorporated into the building design, which helps lower the electric bills; and the residents are responsible for fitting out their own flats, so that they are in control of the budget. The cooperative’s mission is to accommodate families of various formats, covering a multi-generational mix of singles, singleton elderly, single-parent families and families with children, etc. While the majority of them are middle-class and lower-middle-class households who choose to rent their flats, some of them are relatively well off and can purchase the property.

The residents are free to choose between individual flats and communal flats according to their own lifestyle pursuit. The latter come with communal living room and kitchen, and can accommodate 6 to 21 people.

All residents are required to participate in the monthly meetings and play a part in the decision-making process of important policies, such as a bicycle-friendly approach of not providing parking spaces and the management of crops in the garden. Instead of having the architects or the initiating parties dominating the scene, all residents can voice their opinions. Various communal facilities located on the ground floor of the resident buildings, including co-working space, carpentry room, community kitchen, day-care centre, etc., are open to the public, which brings the Spreefeld residents and the neighbours together.

Female co-housing scheme in Vienna: Women no longer bounded by the identities of “mums” and “office ladies”

Architect Sabine Pollak, active in Vienna, has participated in the discussions surrounding women and housing for many years. In 2002, Pallak initiated a women’s housing project, titled [ro*sa]22, which collects the perspectives on housing of women who live alone. Qualities that constitute the female imagination of future housing include small apartments, abundance of open spaces, affordable rent, etc. This women co-living scheme, considered by Pollak a means to empower women, has garnered government support: two sites for constructions and subsidies are provided. It took a total of 7 years to complete the project since it was conceived. Applicants will be informed of the organisation’s visions for the sake of gathering a group of like-minded residents who are willing to contribute to a women-oriented community.

Most of the residents spent the first two years settling down and adapting to the new environment. Later on, the community life grew increasingly vibrant with the emergence of weekend activities within the neighbourhood. Examples include pottery workshops in studio, baby parties in garden, indoor film screenings, etc. The library housing a key collection of feminist books is also a popular communal space. Reading club sessions are hosted to open up discussions on women’s issues and relevant solutions. One of the residents shares her experience of having received lots of respect and encouragement, which stimulated her creativity. Being more open to explore her potentials apart from being a mum and an official lady, she took a step out of her comfort zone to become a photographer.

Housing for immigrant families in Belgium: Spend less and save more

“Being born with a silver spoon in the month” is the common dream of many Hongkongers; owning a house is simply a dream come true. In Brussels, the capital of Belgium, things are similar when it comes to housing. An idiom goes as, “Every Belgian is born with a brick in their stomach”, which means that buying a home is high upon the list of the lifetime goals of many Belgians.

It is sad to see how both Hongkongers and Belgians find owning a house such an unachievable goal because of ever-soaring property prices and inadequate public housing supply to meet people’s demands. Even the locals living in the poor district in Belgium could not afford buying a house, let alone the immigrant newcomers. In view of this housing problem, a community centre put forward a housing initiative catering for immigrant families in collaboration with CIRE, an organisation that defends the rights of refugees and foreigners . The scheme cultivates co-living communities among the immigrants and hosts co-housing-themed workshops; outcomes of workshops and meetings are consolidated to form the basis of the architects’ design direction.

One of the decisions collectively made by the families is the introduction of “passive house” standards, which significantly reduces energy consumption. Passive house buildings are designed to keep the buildings warm in winter and cool in summer, achieving energy efficiency through architectural structure and the use of building materials. Different families also come together and form money-saving groups among themselves. After 7 years of discussions and construction projects, 14 families are now living in their own flats. Years of communication also facilitates the formation of a community with mutual trust and strong bonding. The gap between locals and immigrants is bridged by various activities in the neighbourhood, such as the operation of a community garden and open-to-all street parties.

Image: Internet

你可能對以下吉人吉事有興趣:

You may also be interested in these GUTS Stories: