香港士紳化:從利東街到深水埗|Gentrification in Hong Kong: From Lee Tung Street to Sham Shui Po

舊區更新,改善基層居住環境、提升舊區價值,本來或許是一番好意,但它又總伴隨著「士紳化」的批評,社區網絡被瓦解、窮人被趕到更偏遠更貧窮的地方。現今在香港,幾乎每一個老區都正在經歷活化的過程,若吉人想探討士紳化,該從何說起?

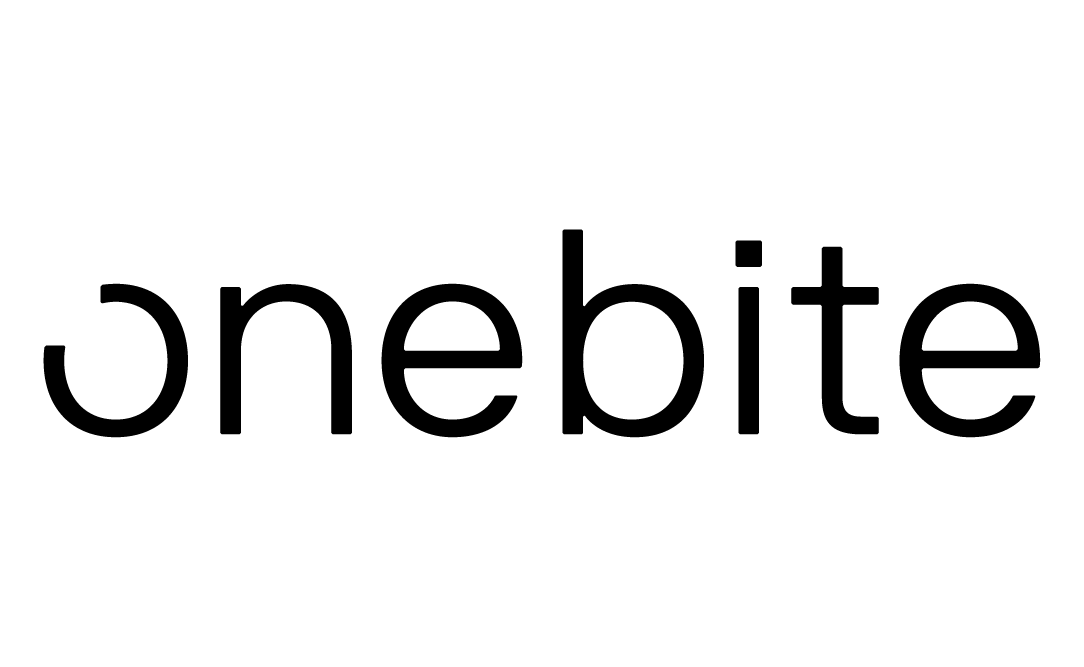

香港最先引起「士紳化」討論的事件,該要追溯至灣仔利東街的舊樓清拆重建。利東街並不是香港首個重建項目,但直至2006年開始,中環天星碼頭、皇后碼頭先後清拆,掀起香港保育抗爭浪潮,同期發生的灣仔利東街重建,部分居民和商店拒絕重建,爭取的不是要求更多賠償,而是拒絕鄰里關係被連根拔起、捍衛社區的文化經濟價值。當時,不少人憂慮利東街將被士紳化,原本為草根階層生活場所的舊街道,變成樓價飛升、瞄準中產買家的新樓盤。結果,抗爭不果,利東街清拆重建為「囍匯」,灣仔嚴重士紳化:巿建局2004年公佈利東街的清拆賠償呎價為$4,079,9年後重建成的「囍匯」,開售呎價為$19,776,升幅近4倍。2009年,有地產經紀談及重建項目密集的灣仔唐樓,因為重建後升價數倍,以致唐樓樓價亦升逾五成。換言之,區內的草根階層,即使所住的唐樓未有重建計劃,也因為無法負擔租金而提早被逼搬到其他區域重新適應生活。

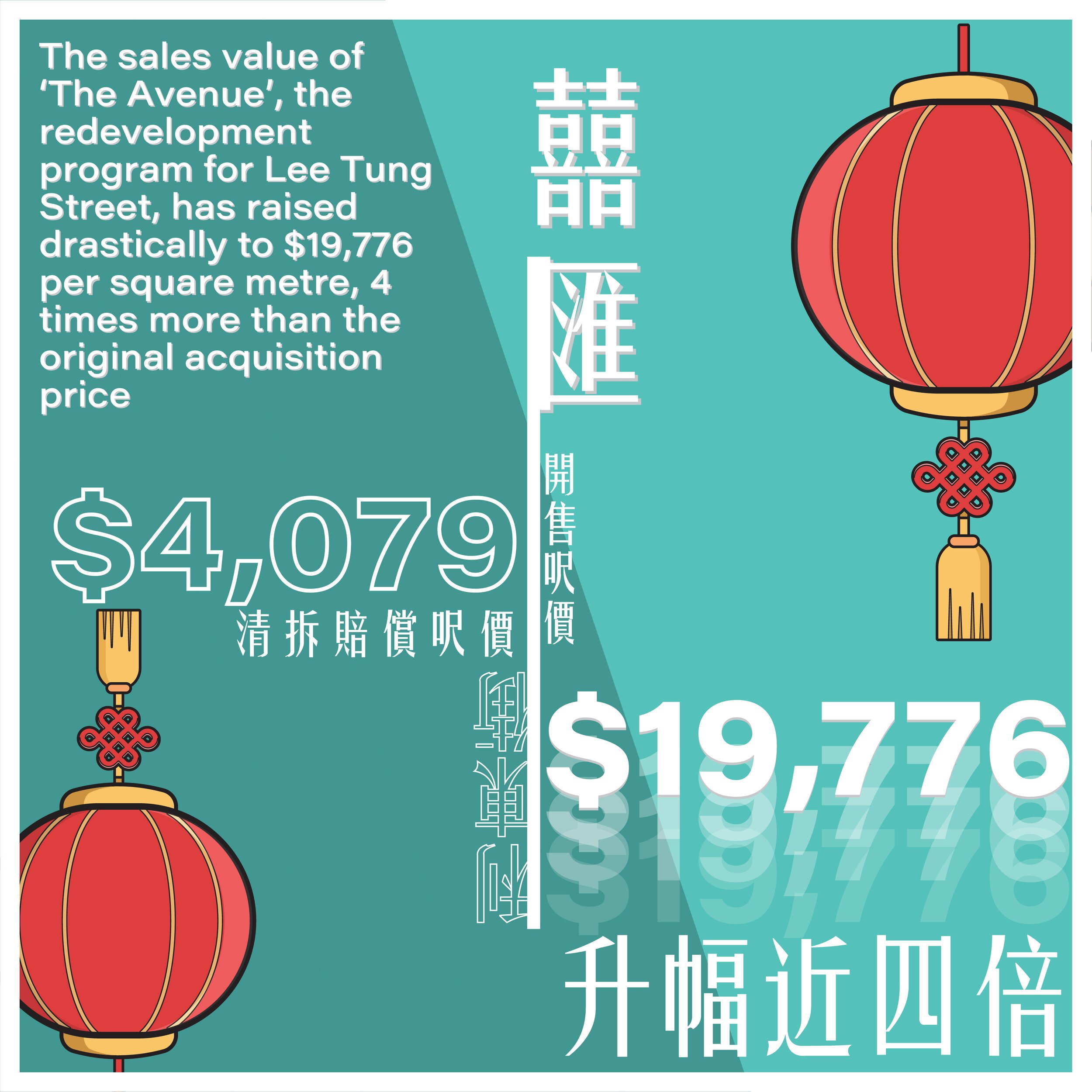

此後,觀塘成了灣仔之後的大規模重建區域。而因為港鐵版圖的擴展,以往交通只靠巴士、小巴的舊區如西營盤,亦經歷了由基建規劃帶動的士紳化。時至今日,即將面臨翻天覆地變化的,有大規模發展計劃、鐵路落成數年的錦上路,以及有不少重建項目如箭在弦,包括明年有港鐵直達的土瓜灣。

因巿區重建帶動的士紳化,在香港各區遍地開花;另一邊廂,藝廊、文藝小店遷進舊區而間接推動的士紳化,也開始在上環的太平山街出現。太平山街作為香港最古老的華人區,因為1894年爆發鼠疫而夷平了一部分房屋,興建卜公花園。由於位處半山,區內仍然保留具歷史痕跡的唐樓、石梯、廟宇與醫院。大約在2010年,由於中環蘇豪區租金飈升,不少畫廊、手作店等開始向西移至這裏,一度營造成文藝小區,周末吸引不少年輕人流連,唐樓相繼翻新成有品味的建築、店舖換來更高檔的藝廊進駐。不過,太平山街一帶近年租金大幅上升,很多年輕藝術家無法生存,被逼搬遷。

有相同經歷的地區,還有位處於獅子山腳下的深水埗。深水埗在1940至50年代,成為不少內地難民的落腳地,勞動人口增加和急速發展的工業,令這裡成為工場與山寨廠的集中地,其後衍生出大量批發店,售賣製衣和電子等材料、配件。同樣大約在2010年,深水埗開始出現零星的文藝旅館、手作店,創意小店,更擴展至大南街一帶,及後引起了一輪士紳化的討論:街道年輕化、品味化會否引致租金上升?當地居民會否被逼放棄原有生活?至今,深水埗仍是香港最多基層居住的地區之一,但近年改變亦不少,文青人流讓文藝小店找到生存空間之餘,亦引起發展商開發的興趣,例如把唐樓翻新成為服務式公寓,甚至唐樓群之間已插入不少新建豪宅。

最近,深水埗因為「Shamshuipo is the new Brooklyn」再掀起熱議。它是否會發展成如Brooklyn的潮人聖地,仍是未知數;但不少吉人已意識到,若深水埗要變成新Brooklyn,必須避免步Brooklyn被大規模規劃的後塵,逼走原居民。深水埗或許是一個很好的實驗場所,考驗新興的文創產業,如何與原有的社區共存相處,成為一樁吉事。

相片來源:網上圖片、城市大學資料庫

地點:香港

Gentrification in Hong Kong: From Lee Tung Street to Sham Shui Po

Urban regeneration presents opportunities and challenges to old neighbourhoods. While it creates new business opportunities and a better environment, it might also introduce gentrification that disrupts the original community. As Hong Kong is undergoing rapid development, urban regeneration seems to be the destiny for every old neighbourhood, perhaps we can take this opportunity to take a closer look at how gentrification is playing out in our city!

Wan Chai’s famous ‘Wedding Card Street’ Lee Tung Street is the very first urban redevelopment project that provoked a discussion on gentrification in the city. After losing both the Central Star Ferry Pier and the Queen’s pier to demolition for land reclamation since 2006, Lee Tung Street was a wakeup call for people to value local heritage above economic value. However, Lee Tung Street was eventually cleared out in 2007 by the Urban Renewal Authority for redevelopment, which drastically impacted Wan Chai’s cost of rent. In 2009, real estate agents reported that the value of surrounding old tenement buildings has surged for 50%, forcing grassroots tenants to leave the area because of unaffordable rent. Nine years later, a new private estate ‘The Avenue’ debuted in the redeveloped area, it is not surprising that the sales value raised drastically to $19,776 per square metre, 4 times more than the original acquisition price.

Kwun Tong was another district designated for large-scale redevelopment after Wan Chai. Development of infrastructure, like the extension of MTR to old neighbourhoods like Sai Ying also brough gentrification to the area. In the near future, Kam Sheung Road in Yuen Long, and To Kwa Wan will soon be impacted as the railway reaches the districts.

Another typical case of gentrification in Hong Kong is Tai Ping Shan Street in mid-levels. Being Hong Kong’s oldest area for Chinese community, Tai Ping Shan Street is a place with rich history and heritage such as stone staircases, temples and historical traces, etc. In 2010, as the rent of Soho in Central skyrocketed, galleries and small handcrafted shops gradually moved westward to Tai Ping Shan Street for a relatively cheaper rent. The area was transformed into a vibrant cultural hub, attracting young visitors on weekends. The buildings was successively renovated into high-end galleries, old tenement buildings were redesigned into stylish apartments. The rent eventually spiked and it was almost as if planned destiny that the artists were then forced to move out as they could no longer afford the rent.

Recently, Sham Shui Po is facing a similar challenge. As a historic blue-collar district since 1940s, the district was once the home for refugees from the mainland. It later became a heaven of small-scale factories and wholesale distribution centre following the rapid economic development in Hong Kong. Since 2010, arty hostels and creative craft shops slowly emerged which initiating a discussion on whether gentrification is going to turn the area around. As the streets are being rejuvenated, Sham Shui Po is under spotlight on its subsequent impact to the cost of rent, and how would that impact the original residents. Do people need to change their lifestyle completely? As we observe for now, Sham Shui Po is still Hong Kong’s poorest district. While it continues to provide a breathing space for small scale art shops, it is already attracting developers’ aggression to turn the old tenement houses into serviced apartment.

The latest discussion on the redevelopment of the area is whether ‘Sham Shui Po is the new Brooklyn’. A new and ‘successful’ Brooklyn, as we all know, must avoid stepping into the dark holes of gentrification, replacing existing residents with the upper class. Sham Shui Po may be a good ground for experiment, for us to understand how new cultural industries and the original community could coexist in the same neighbourhood.

Photo source: Internet, City University of Hong Kong Archive

Location: Hong Kong

你可能對以下吉人吉事有興趣:

You may also be interested in these GUTS Stories: